The Impact of Protein Binding on Analyte Recovery for Small-Molecule Pharmaceuticals

January 12, 2026

Reviewed by Our Phenomenex Team

Bioanalytical methods are essential for quantifying drugs and metabolites in biological matrices, supporting the evaluation of bioavailability, bioequivalence, and dosage requirements. According to the free drug theory, only the unbound fraction (fu) is pharmacologically active and contributes to pharmacokinetic parameters such as distribution, absorption and clearance. Plasma proteins albumin and α1-acid glycoprotein, which account for about 6–8% of plasma by weight, can reversibly bind many drugs most notably leaving only the small free fraction available to cross biological membrane barriers and undergo clearance. Generally,absorption and clearance decreases as protein binding increases, since only the unbound drug can be absorbed and eliminated.

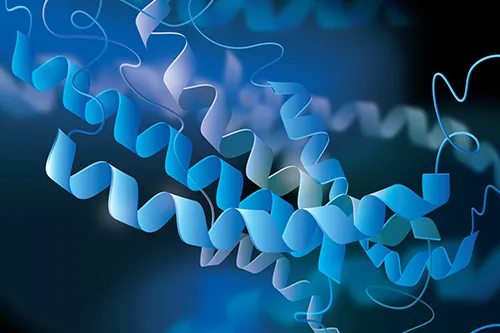

What is Protein Binding?

Protein binding refers to the reversible, non-covalent interaction between drugs and plasma proteins. After entering systemic circulation, drugs may exist in either bound or unbound form, depending on their affinity for proteins such as albumin, α1-acid glycoprotein (AAG), lipoproteins, and globulins. Acidic and neutral drugs primarily bind to albumin, whereas basic drugs preferentially bind to AAG.

Protein binding influences both pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, since only the unbound fraction (free drug) is pharmacologically active, able to cross membranes, distribute into tissues, and undergo adsorption, metabolism and clearance.

Because biological matrices are complex, efficient sample preparation is critical. Common strategies include liquid–liquid extraction, solid-phase extraction, and protein precipitation, with protein precipitation being the most widely used due to its simplicity, speed, and suitability for high-throughput LC–MS/MS analysis. The choice of precipitant organic solvent, acid, or salt depends on the drug’s chemical properties and binding interactions, as disrupting drug–protein complexes is necessary for accurate quantitation.

How Protein Binding Affects Analyte Recovery?

The effect of protein binding can reduce analyte recovery, as drugs bound to plasma proteins are not readily extractable during sample preparation. However, pinpointing the cause can be difficult due to overlapping and complex factors. A tiered scheme is proposed to systematically eliminate irrelevant sources and prioritize the identification and optimization of the most common and easily identifiable causes of analyte loss.

Protein binding influences analyte recovery in the following ways:

- Apparent Analyte loss: Analyte losses can occur at any stage of sample preparation, making it essential to identify their sources to improve recovery. Because only the unbound fraction of a drug is readily available for extraction, highly protein-bound compounds may show lower recovery if binding is not adequately disrupted during sample preparation. This can lead to underestimation of drug concentration in the sample.

- Matrix effects and nonspecific losses: During extraction and isolation, coeluting endogenous components (especially phospholipids) can cause ion suppression or enhancement in LC–MS/MS analysis. Nonspecific binding to labware (vials, pipette tips, filters) further contributes to analyte loss, particularly for lipophilic drugs.

- Variability in recovery: Protein binding is sensitive to changes in protein levels, pH, and ionic strength. For example, α1-acid glycoprotein (AAG, ~38–48 kDa) normally circulates at 12–31 μM but can rise to ~60 μM in certain disease states. Such variations contribute to inter-assay variability in unbound drug measurements. In contrast, intra-assay reproducibility is generally well controlled in validated assays. Additional variability may arise from assay-specific factors (e.g., solvent effects, matrix composition) and compound-specific issues (e.g., adsorption, detector linearity).

Systematic troubleshooting approaches are recommended to separate protein binding–related issues from other recovery losses, enabling targeted method optimization.

Techniques to Minimize Analyte Loss Due to Protein Binding

Plasma proteins must be removed from samples to avoid column fouling and ensure reliable assay performance. Several strategies are used during sample prep to mitigate protein binding:

- Disrupting protein–drug binding: Drug–protein binding must often be disrupted during sample pre-treatment, typically by adjusting pH or precipitating plasma proteins.

- Extraction techniques: :Liquid–liquid extraction (LLE), solid-phase extraction (SPE), and supported liquid extraction (SLE) are commonly employed for sample cleanup and analyte enrichment. Since many drugs bind to plasma proteins, disrupting protein–drug complexes is often required to release the analyte and ensure efficient recovery.

- Low-binding labware: Use of low-adsorption or low-binding glasswares helps reduce nonspecific adsorption of analytes to tubes and pipette tips. In some assays, surfaces can be blocked with agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA) to further minimize binding, although this is less common in LC–MS/MS workflows due to potential contamination.

- Nanomaterial-based approaches: Novel approaches such as the use of bare magnetic nanoparticles for deproteination, provide a cost-effective and efficient way to free protein-bound drugs without centrifugation.

FAQs

How can you detect if poor recovery in your method is due to protein binding?

A strong clue to detect that poor recovery is due to protein binding is a big drop in recovery in the matrix versus the standard.

Can protein binding be adequately eliminated during sample preparation?

Protein binding can be reduced during sample prep. However, it cannot be eliminated completely without disturbing the equilibrium. Techniques such as protein precipitation, ultrafiltration, the addition of displacement agents, pH/ionic strength adjustments, or the use of organic solvents or heat can liberate the analyte.

Is protein binding considered during regulatory method validation?

Yes, bioanalytical method development ensures that an assay is designed, optimized, and validated for its intended purpose. Sponsors are expected to understand the analyte’s properties, such as metabolism and protein binding, and apply this knowledge when developing methods. Key parameters like accuracy, precision, recovery, stability, and matrix effects are optimized to ensure the method meets regulatory validation standards.

Which proteins are most commonly involved in analyte binding?

The proteins most commonly involved in analyte binding are albumin and α-1-acid glycoprotein (AAG), since they are the primary plasma proteins that drugs interact with. Albumin mainly binds acidic and neutral compounds, while α-1-acid glycoprotein has a higher affinity for basic drugs. Lipoproteins and globulins can also contribute, though to a lesser extent.

Does protein binding affect all analytes equally?

No, protein binding does not affect all analytes equally, it depends on each compound’s physicochemical properties such as charge, lipophilicity, and molecular size. Some drugs may bind strongly to plasma proteins like albumin or AAG, while others remain mostly unbound. As a result, the extent of protein binding and its impact on distribution, absorption, metabolism and bioavailability vary widely between analytes.